Chief Editor

Chief Editor

We don’t talk about it enough, that their surname is “Fury”.

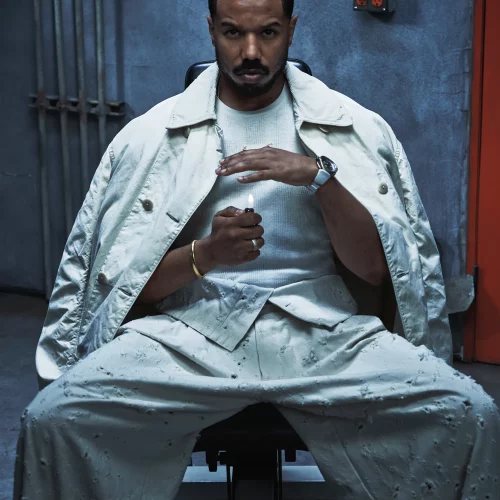

We don’t talk about it enough, that their surname is “Fury”. We just let it happen. The father: “Big” John Fury, the man I am currently bending inelegantly beneath the top line of a ring rope to meet, and then, of course, the sons: Tyson, WBC Heavyweight Champion of the World; Tommy, a man whose job it is for some reason to beat up YouTubers for extreme amounts of money; Roman, a promising amateur who is quietly putting his head down and getting his rounds in; John Jr. and Shane, cackling in the background after every Fury victory. Big John is tremendously, well, big – 6ft 3in – but with an aura many times larger than that, today sporting an Aladdin villain-style white goatee of surprising intricacy beneath those heavy lidded, piercing eyes, somewhere between supermodel-striking and body-horror threatening.

He is wearing, as he often does in public, Tyson Fury-branded athleisure wear and a Tyson Fury-branded hat. We’re at a spa hotel in Macclesfield, which for five days a week is the site of Tommy’s training camp for his bout with KSI. The whole place crackles with Fury energy: hotel guests in white dressing gowns whisper about the possible presence of Tyson, golfers mill around the clubhouse nearby craning to see a glimpse of John or one of his many large strong boys, men in Gypsy King-branded merchandise, tight on the biceps, sit staring disinterestedly at Premier League Years outside our interview room, ready to assemble into formation at a croak of Fury’s command. The car park is stuffed with really, really, really nice cars. John politely refuses a publicist’s offer of water – “I’ve got one here – plenty left in that. I’m alright, me” – and rustles with impeccable, old-school manners.

Ryan Mole

Here’s a man who, over the course of his son’s boxing careers, has made a name out of being an ultra-hard meme-dad at the side of every press conference and post-fight ring invasion: the man who took his top off in an arena in Dubai to threaten Jake Paul; the man who pounded like a wild dog against a plexiglass screen during a recent KSI weigh-in, seemingly impervious to the idea that he couldn’t actually reach him; the man who declared he had “the best pair of bollocks in all of the UK,” and who had the boys insured in 2020 for £10 million; the man who, in At Home with the Furys, seems to be constantly told he’s going on holiday, then gets told that no, he’s not actually going on holiday; the man who, in a YouTube video I regularly make people watch, made a strange grey slurry for a visibly scared boxing journalist while murmuring about his daily running routine. The man in front of me – amiably eking out a room-temperature bottle of water to save a PR having to fetch him a new one from a bar 10ft away – is, well: not that. Very, very not that.

“I find there’s no better evening than a cheese and onion sandwich, Hammer House of Horror, feet up, dim lights,” he says, as the chaotic whirl of people that constantly surrounds him cedes for a moment, and we speak for a still, uninterrupted hour-and-a-half. “That’s me.” People linger around John Fury – he’d spent the morning recording a podcast about mental health, and as the previous team pack up and wind wires around us, they are still in awe of him, coming back for third and fourth goodbye handshakes, waiting at attention for a few final words of wisdom. He starts a lot of sentences with, “Listen,” and a big heavy pause, and you lean in and, yes, listen, listen to what he has to say, listen harder than you’ve ever listened before. Out of context, it’s strange that we know this much about any athlete’s dad, but up close he is magnetic, impossible to ignore, dripping with a heavy tungsten feeling of respect. Talking to John Furyisn’t like talking to a man in the vortex of elite-level sport, it’s like talking to a village elder, or some head of an ancient clan, as they stoke a fire quietly with a stick and warn you that clean living is the only sure deterrent against monsters.

His new book, When Fury Takes Over, is part memoir and part the most interesting chat you’ve ever had with a random bloke at the pub, and takes some surprising zigs. (There is a long section at the back where John pontificates on the best boxers to ever box and the best fights ever seen; there are also sections about depression, ghosts, and an all-encompassing simple life philosophy called “Keep What You Need, Not What You Want”).

Born to a Traveller family in Ireland, Fury spent a lot of his formative years moving around the Midlands before an adolescent trip to Borstal ended in a head-spinningly wacky escape caper – but when Big John starts to find his sheer Big Johnness is when the book starts to come alive. He found a strange sureness and pride in fighting as a young man – there are a number of stories of a 16-year-old John Fury knocking the teeth out of older, taller men – and a fascinatingly bizarre account of “the most difficult fight” he ever had, against a man he was trying to sell a rug to as a young travelling salesman. “We walked to a nearby deserted playground,” Fury writes, “where there were a few swings, a slide and one of those spinning roundabouts. We went straight to it and it was a hard tussle. I lost a tooth and had to have multiple stitches in my lip, while he lost half an ear and was temporarily blind in one eye.” After the man finally cries that he’s beat, they sit on the roundabout and he asks John, “Listen, do you want a glass of fizzy pop?” The post-fight drink of choice was Tizer.

Ryan Mole

After a short stint in prison, John found work as an “enforcer” and dabbled with “the fancy” world of professional boxing, but started too late – and was too ostracised for his Gypsy heritage– to make the impact his sons have gone on to make. “Making it as an international champion involves a cosmic set of conditions beyond your diet and fitness level,” he writes. “Without someone looking out for me, I managed to get to title level. Sometimes I idly speculate how far I could’ve got if I’d enjoyed the benefits of sponsorship and career guidance.”

By then, his family was growing – Tyson, the son who would go on to become the champion who would truly make Big John’s name and legacy, had already been born – and he had other responsibilities beyond being punched in the face by WBO title contenders. In When Fury Takes Over, there’s a noticeable gap between John’s life post-boxing and pre-fame – it’s basically work, family, work, family, a surprisingly poignant trip to Canada and then an account of his second stint in prison between 2011 and 2015 – but it’s been eight years now since Tyson’s all-conquering fight against Wladimir Klitschko; eight years since we’ve known John Fury’s name about as much as Tyson’s.

His sons’ arena fights exhaust him – not from the emotion or the focus, but from the noise. “I’ve never been to a football match in my life, because I couldn’t stand the noise. Any big stadium, I’m sort of like, When can I leave? The noise levels are harder than the fight. When I leave a place like Wembley, 60,000 people – I feel like I’ve got a hangover. I feel like I’ve been on the beer for a week! It’s mentally draining.” He’s not good at taking holidays – “I hate flying. Hate it. If I could drive to Saudi Arabia, I’d set off going right now” – but craves tranquillity when not in the heat of a training camp. “I’ve got an old shepherd’s hut, an old military caravan sort of thing, and I tow it to nice tranquil places. Nice scenery. And I spend a few days, just me and the dog and a canary I’ve got, and just chill out. Cooking outside on the barbecue. Few nice pots of tea. Speak to some nice passersby, nice conversations. That’s my outlet, that: I enjoy it more than going to Spain.”

He’s not a huge fan of technology – over the course of our 90 minutes together, he blames at least four modern ills on the existence of Instagram – and only got a smartphone this year when gifted one on the way out of Saudi Arabia by Prince Khalid bin Abdulaziz. “I had an old Nokia phone for 25 years. Black thing. He kept looking at me like, How can you survive with that?” and you feel like he craves an old-fashioned way of life in more ways than one. He laments a certain distance with his sons. “At some point, you don’t want to be separated from your children. When they’ve got partners – they’ve got girlfriends, they’ve got wives – you’re sort of like, you know, parting company. But I don’t want to part there.” He bristles at modernity getting in the way of that. “I’m looking at the relationship with my mother and father – I was never away, never away. I seen my mother and father every day till the day they died. I used to go Sunday lunch there every weekend – she used to call me up, say, ‘I’ve made you a nice rabbit pie, son, I’ve made you a nice broth’ – bang, I was there. I enjoyed me mother and father’s company. But I don’t get that from my sons, I don’t get it.”

Ryan Mole

When Fury Takes Over is dedicated to his largest son – “For my son Tyson, without whose remarkable achievements in boxing there would be no book or such interest in the Fury family” – and their legacy is intrinsically shared. There’s the much-told apocryphal story of John rushing to the hospital when a premature Tyson was newly born, just a pound in weight, and he declared that he would be “nearly 7ft tall, 20 stone, and the next heavyweight champion of the world.” It’s a story John tells again for me – “Listen,” – and, hearing it in real life, you believe every second of it: you are stoking the fire in a year before time, and a 7ft warrior emerges from the woods. There’s the story of Tyson’s mid-career comeback from retirement, when he ballooned in weight and wrestled darkly with his own mental health, then Bic’d his head bald and beat Deontay Wilder two times in a row. Tyson has been outspoken about men’s mental health since, and there are mentions of it in John’s book, too – he talks about both the “black fog” and the “red mist” affecting his moods throughout adulthood, and calls himself a “mental health sufferer” many times over. Was Tyson’s struggle with mental health one that inspired his own, I ask? Has modern classification and language helped him realise something he’d been living with all along?

“Let me put it this way: if it wasn’t for the understanding, and it being more talked about today, I don’t think I’d have been here talking to you now.” His coping mechanism has always been calling people and knowing they’re at the other end of the phone for him. “Like now, if I get into a situation where I think I may not be handling things too well, or letting things get the better of me, I can phone somebody up. I can have a chat to them, and they’re going to direct me. Back in the day my father did it, and my mother, and when they went I thought, I have a problem, here. Because no one was there for me to do it.” During his four years in prison – Fury was convicted in 2011 of wounding with intent – he often visited “the listeners”, lifers whose role it was to work as de facto talking therapists while inside. He struggled to readjust upon release – “I was scared stiff of going outside” – but has now found some coping systems that work. “Listen,” he says, “you know: if you don’t talk, people’s not going to know, are they?” He leans in closer. “How do we spread good vibes? By talking about them!” My audience with the village elder, the ancient man’s man who sired a brood of warriors, is over. I wait to shake his hand five more times before leaving.

When Fury Takes Over is out now.

Life lessons with Big John Fury

We don’t talk about it enough, that their surname is “Fury”. We just let it happen. The father: “Big” John Fury, the man I am currently bending inelegantly beneath the top line of a ring rope to meet, and then, of course, the sons: Tyson, WBC Heavyweight Champion of the World; Tommy, a man whose job it is for some reason to beat up YouTubers for extreme amounts of money; Roman, a promising amateur who is quietly putting his head down and getting his rounds in; John Jr. and Shane, cackling in the background after every Fury victory. Big John is tremendously, well, big – 6ft 3in – but with an aura many times larger than that, today sporting an Aladdin villain-style white goatee of surprising intricacy beneath those heavy lidded, piercing eyes, somewhere between supermodel-striking and body-horror threatening.

He is wearing, as he often does in public, Tyson Fury-branded athleisure wear and a Tyson Fury-branded hat. We’re at a spa hotel in Macclesfield, which for five days a week is the site of Tommy’s training camp for his bout with KSI. The whole place crackles with Fury energy: hotel guests in white dressing gowns whisper about the possible presence of Tyson, golfers mill around the clubhouse nearby craning to see a glimpse of John or one of his many large strong boys, men in Gypsy King-branded merchandise, tight on the biceps, sit staring disinterestedly at Premier League Years outside our interview room, ready to assemble into formation at a croak of Fury’s command. The car park is stuffed with really, really, really nice cars. John politely refuses a publicist’s offer of water – “I’ve got one here – plenty left in that. I’m alright, me” – and rustles with impeccable, old-school manners.

Ryan Mole

Here’s a man who, over the course of his son’s boxing careers, has made a name out of being an ultra-hard meme-dad at the side of every press conference and post-fight ring invasion: the man who took his top off in an arena in Dubai to threaten Jake Paul; the man who pounded like a wild dog against a plexiglass screen during a recent KSI weigh-in, seemingly impervious to the idea that he couldn’t actually reach him; the man who declared he had “the best pair of bollocks in all of the UK,” and who had the boys insured in 2020 for £10 million; the man who, in At Home with the Furys, seems to be constantly told he’s going on holiday, then gets told that no, he’s not actually going on holiday; the man who, in a YouTube video I regularly make people watch, made a strange grey slurry for a visibly scared boxing journalist while murmuring about his daily running routine. The man in front of me – amiably eking out a room-temperature bottle of water to save a PR having to fetch him a new one from a bar 10ft away – is, well: not that. Very, very not that.

“I find there’s no better evening than a cheese and onion sandwich, Hammer House of Horror, feet up, dim lights,” he says, as the chaotic whirl of people that constantly surrounds him cedes for a moment, and we speak for a still, uninterrupted hour-and-a-half. “That’s me.” People linger around John Fury – he’d spent the morning recording a podcast about mental health, and as the previous team pack up and wind wires around us, they are still in awe of him, coming back for third and fourth goodbye handshakes, waiting at attention for a few final words of wisdom. He starts a lot of sentences with, “Listen,” and a big heavy pause, and you lean in and, yes, listen, listen to what he has to say, listen harder than you’ve ever listened before. Out of context, it’s strange that we know this much about any athlete’s dad, but up close he is magnetic, impossible to ignore, dripping with a heavy tungsten feeling of respect. Talking to John Furyisn’t like talking to a man in the vortex of elite-level sport, it’s like talking to a village elder, or some head of an ancient clan, as they stoke a fire quietly with a stick and warn you that clean living is the only sure deterrent against monsters.

His new book, When Fury Takes Over, is part memoir and part the most interesting chat you’ve ever had with a random bloke at the pub, and takes some surprising zigs. (There is a long section at the back where John pontificates on the best boxers to ever box and the best fights ever seen; there are also sections about depression, ghosts, and an all-encompassing simple life philosophy called “Keep What You Need, Not What You Want”).

Born to a Traveller family in Ireland, Fury spent a lot of his formative years moving around the Midlands before an adolescent trip to Borstal ended in a head-spinningly wacky escape caper – but when Big John starts to find his sheer Big Johnness is when the book starts to come alive. He found a strange sureness and pride in fighting as a young man – there are a number of stories of a 16-year-old John Fury knocking the teeth out of older, taller men – and a fascinatingly bizarre account of “the most difficult fight” he ever had, against a man he was trying to sell a rug to as a young travelling salesman. “We walked to a nearby deserted playground,” Fury writes, “where there were a few swings, a slide and one of those spinning roundabouts. We went straight to it and it was a hard tussle. I lost a tooth and had to have multiple stitches in my lip, while he lost half an ear and was temporarily blind in one eye.” After the man finally cries that he’s beat, they sit on the roundabout and he asks John, “Listen, do you want a glass of fizzy pop?” The post-fight drink of choice was Tizer.

Ryan Mole

After a short stint in prison, John found work as an “enforcer” and dabbled with “the fancy” world of professional boxing, but started too late – and was too ostracised for his Gypsy heritage– to make the impact his sons have gone on to make. “Making it as an international champion involves a cosmic set of conditions beyond your diet and fitness level,” he writes. “Without someone looking out for me, I managed to get to title level. Sometimes I idly speculate how far I could’ve got if I’d enjoyed the benefits of sponsorship and career guidance.”

By then, his family was growing – Tyson, the son who would go on to become the champion who would truly make Big John’s name and legacy, had already been born – and he had other responsibilities beyond being punched in the face by WBO title contenders. In When Fury Takes Over, there’s a noticeable gap between John’s life post-boxing and pre-fame – it’s basically work, family, work, family, a surprisingly poignant trip to Canada and then an account of his second stint in prison between 2011 and 2015 – but it’s been eight years now since Tyson’s all-conquering fight against Wladimir Klitschko; eight years since we’ve known John Fury’s name about as much as Tyson’s.

His sons’ arena fights exhaust him – not from the emotion or the focus, but from the noise. “I’ve never been to a football match in my life, because I couldn’t stand the noise. Any big stadium, I’m sort of like, When can I leave? The noise levels are harder than the fight. When I leave a place like Wembley, 60,000 people – I feel like I’ve got a hangover. I feel like I’ve been on the beer for a week! It’s mentally draining.” He’s not good at taking holidays – “I hate flying. Hate it. If I could drive to Saudi Arabia, I’d set off going right now” – but craves tranquillity when not in the heat of a training camp. “I’ve got an old shepherd’s hut, an old military caravan sort of thing, and I tow it to nice tranquil places. Nice scenery. And I spend a few days, just me and the dog and a canary I’ve got, and just chill out. Cooking outside on the barbecue. Few nice pots of tea. Speak to some nice passersby, nice conversations. That’s my outlet, that: I enjoy it more than going to Spain.”

He’s not a huge fan of technology – over the course of our 90 minutes together, he blames at least four modern ills on the existence of Instagram – and only got a smartphone this year when gifted one on the way out of Saudi Arabia by Prince Khalid bin Abdulaziz. “I had an old Nokia phone for 25 years. Black thing. He kept looking at me like, How can you survive with that?” and you feel like he craves an old-fashioned way of life in more ways than one. He laments a certain distance with his sons. “At some point, you don’t want to be separated from your children. When they’ve got partners – they’ve got girlfriends, they’ve got wives – you’re sort of like, you know, parting company. But I don’t want to part there.” He bristles at modernity getting in the way of that. “I’m looking at the relationship with my mother and father – I was never away, never away. I seen my mother and father every day till the day they died. I used to go Sunday lunch there every weekend – she used to call me up, say, ‘I’ve made you a nice rabbit pie, son, I’ve made you a nice broth’ – bang, I was there. I enjoyed me mother and father’s company. But I don’t get that from my sons, I don’t get it.”

Ryan Mole

When Fury Takes Over is dedicated to his largest son – “For my son Tyson, without whose remarkable achievements in boxing there would be no book or such interest in the Fury family” – and their legacy is intrinsically shared. There’s the much-told apocryphal story of John rushing to the hospital when a premature Tyson was newly born, just a pound in weight, and he declared that he would be “nearly 7ft tall, 20 stone, and the next heavyweight champion of the world.” It’s a story John tells again for me – “Listen,” – and, hearing it in real life, you believe every second of it: you are stoking the fire in a year before time, and a 7ft warrior emerges from the woods. There’s the story of Tyson’s mid-career comeback from retirement, when he ballooned in weight and wrestled darkly with his own mental health, then Bic’d his head bald and beat Deontay Wilder two times in a row. Tyson has been outspoken about men’s mental health since, and there are mentions of it in John’s book, too – he talks about both the “black fog” and the “red mist” affecting his moods throughout adulthood, and calls himself a “mental health sufferer” many times over. Was Tyson’s struggle with mental health one that inspired his own, I ask? Has modern classification and language helped him realise something he’d been living with all along?

“Let me put it this way: if it wasn’t for the understanding, and it being more talked about today, I don’t think I’d have been here talking to you now.” His coping mechanism has always been calling people and knowing they’re at the other end of the phone for him. “Like now, if I get into a situation where I think I may not be handling things too well, or letting things get the better of me, I can phone somebody up. I can have a chat to them, and they’re going to direct me. Back in the day my father did it, and my mother, and when they went I thought, I have a problem, here. Because no one was there for me to do it.” During his four years in prison – Fury was convicted in 2011 of wounding with intent – he often visited “the listeners”, lifers whose role it was to work as de facto talking therapists while inside. He struggled to readjust upon release – “I was scared stiff of going outside” – but has now found some coping systems that work. “Listen,” he says, “you know: if you don’t talk, people’s not going to know, are they?” He leans in closer. “How do we spread good vibes? By talking about them!” My audience with the village elder, the ancient man’s man who sired a brood of warriors, is over. I wait to shake his hand five more times before leaving.

When Fury Takes Over is out now.